Karl Marx’s Methodology: Unveiling His Materialistic Conception of History

Karl Marx's Methodology: Unveiling His Materialistic Conception of History

Karl Marx’s Methodology: Unveiling His Materialistic Conception of History

Karl Marx, a revolutionary thinker and philosopher, introduced a groundbreaking methodology to the social sciences during his time. His innovative concepts and hypotheses left an indelible mark on the fields of history, political science, and sociology. In this article, we will delve into Marx’s methodology, with a particular focus on his materialistic conception of history and his views on social conflict and change.

Marx’s Materialistic Conception of History

Marx’s methodology is anchored in his materialistic conception of history, which serves as the cornerstone of his social analysis. According to Marx, the driving force behind historical evolution is the manner in which human beings interact with nature to meet their fundamental survival needs. The production of material life is considered the first pivotal historical act in Marx’s framework. Even after satisfying their primary needs, humans continue to experience dissatisfaction because new, secondary needs emerge once the primary ones are met.

As individuals strive to fulfill these needs, they engage in social relationships with one another. In the process, as material life becomes increasingly complex, society undergoes a transformation. The division of labor emerges, leading to the formation of distinct classes within society—namely, the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

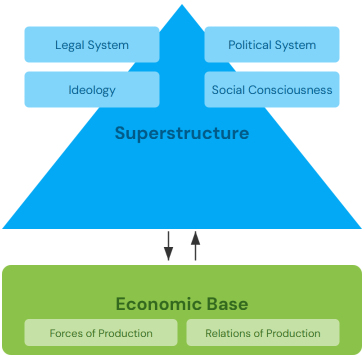

Marx emphasizes the economic “infrastructure” as the key shaping force for the rest of society. The specific mode of production dictates the relations of production, which, in turn, uphold the entire cultural superstructure. This holistic approach to society is a crucial methodological contribution by Marx, highlighting the interconnectedness of various social components. Social groups, institutions, beliefs, and doctrines are interrelated and should be studied as such. Nonetheless, the economic system ultimately holds the decisive role in shaping the features of the superstructure.

Marx applies his materialistic conception of history by examining human society’s history in distinct stages, each marked by a specific mode of production. From these modes of production stem unique relationships and class antagonisms that characterize each historical phase. His theory of “historical materialism” provides a detailed framework for understanding these stages and their dynamics. Marx is a relativizing historicist, rooting social relationships and ideas within specific historical contexts, and acknowledging the qualitative differences in class struggles across epochs.

Social Conflict and Social Change

Early sociology, notably influenced by the ideas of Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer, leaned towards the doctrine of evolutionary change, emphasizing peaceful growth as the primary driver of societal progress. In this context, social order and harmony were considered the norm, while disorder and conflict were viewed as pathological.

Marx’s contributions to sociological thought stand in stark contrast to this prevailing perspective. He asserts that societies are inherently mutable systems, with change primarily propelled by internal contradictions and conflicts. Each historical stage is marked by its unique contradictions and tensions, which intensify over time, eventually leading to the breakdown of the existing system and the emergence of a new one. In essence, Marx sees conflict not as something detrimental but as a creative force, the engine of progress.

Marx’s Notion of ‘Praxis’

A distinctive aspect of Marx’s methodology is his concept of ‘praxis.’ Unlike many sociologists who sought to maintain a separation between sociological theory and political ideology, Marx unites theory and political activism in his work. He openly expresses his critique of capitalist society, which he views as an inhumane system of exploitation. Marx anticipates the system’s eventual collapse under the weight of its internal contradictions, paving the way for the birth of a classless, communist society free from such contradictions. Marx advocates ‘praxis,’ which involves using theory as a tool for practical political action. This methodology aims not only to understand society but also to anticipate and actively contribute to its transformation.

The concept of ‘praxis‘ is rooted in the Greek term for action or activity, which was further developed and refined in European philosophy, particularly by thinkers like Aristotle, Francis Bacon, and Immanuel Kant. Kant, for instance, distinguished between “pure” and “practical” reason, highlighting the primacy of practical philosophy. Marx’s ‘praxis‘ represents the unification of philosophy and revolutionary action, ultimately aimed at transforming the world. He views ‘praxis‘ as a means to eliminate alienation, turning labor into non-alienative, creative self-activity.

In conclusion, Karl Marx’s methodology has left an indelible mark on the social sciences, introducing novel concepts and hypotheses that continue to influence the fields of history, political science, and sociology. His materialistic conception of history, emphasis on the role of conflict in social change, and the concept of ‘praxis‘ have all contributed to a deeper understanding of society and its evolution. Marx’s holistic approach to studying society and his recognition of the distinctive features of each historical stage further enrich the social sciences, emphasizing the interconnectedness of various social components.

Karl Marx’s Methodology: Unveiling His Materialistic Conception of History Read More »