Q. Indian Constitution has conferred the amending power on the ordinary legislative institutions with a few procedural hurdles. In view of this statement, examine the procedural and substantive limitations on the amending power of the Parliament to change the Constitution.

UPSC Mains 2025 GS2 Paper

Model Answer:

The Indian Constitution empowers Parliament to amend it through Article 368, but this power operates within carefully designed procedural requirements and judicially-evolved substantive boundaries. The framers rejected both extreme rigidity and flexibility, creating a nuanced multi-tiered amendment process that balances adaptability with constitutional sanctity.

Procedural Limitations: A Graduated Approach

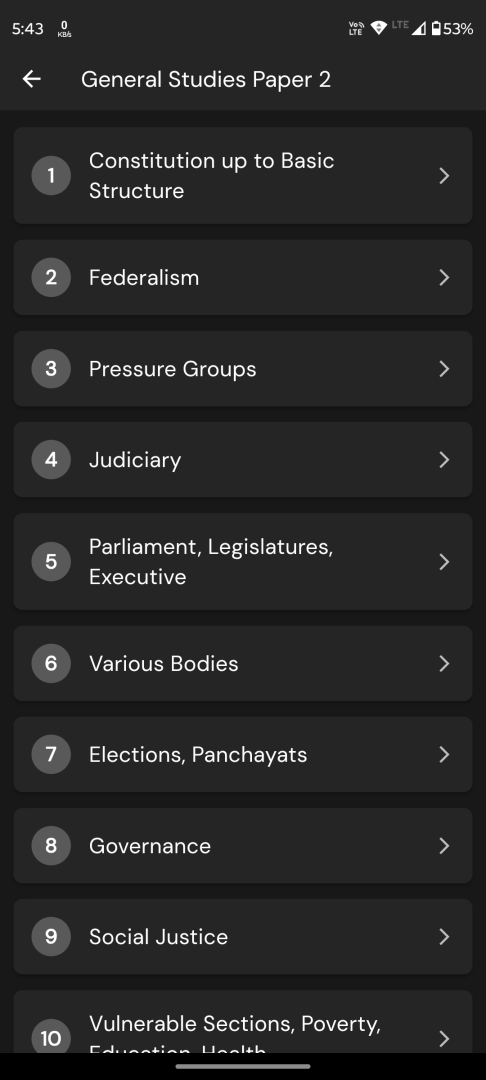

The Constitution prescribes three distinct amendment procedures based on the provisions being modified:

Simple Majority: Certain provisions like citizenship laws, state boundaries (Telangana formation, 2014), and administrative matters require only ordinary legislative majority, though these aren’t formally constitutional amendments under Article 368.

Special Majority: Most constitutional provisions demand a stringent special majority requiring:

• Majority of total membership of each House

• Two-thirds majority of members present and voting

• No provision for joint sitting in case of deadlock

Special Majority with State Ratification: Federal provisions necessitate additional ratification by at least half of state legislatures through simple majority. These include:

• Distribution of legislative powers (Seventh Schedule)

• Representation of states in Parliament

• Supreme Court and High Courts jurisdiction

• Article 368 itself

This ensures federal consensus on matters affecting Centre-State relations. Additionally, constitutional amendment bills cannot originate in state legislatures, and President’s assent, though mandatory, cannot be withheld.

Substantive Limitations: Basic Structure Doctrine

The judiciary has evolved substantive limits through the Basic Structure doctrine, crystallized in Kesavananda Bharati case (1973). Parliament cannot destroy the Constitution’s essential features, including:

• Supremacy of Constitution

• Democratic and republican character

• Secularism and federalism

• Judicial review and rule of law

• Separation of powers

The Minerva Mills case (1980) struck down the 42nd Amendment’s attempt to override this doctrine, reaffirming that Parliament’s amending power itself is limited. This prevents constitutional democracy from being undermined through amendments (NJAC struck down, 2015).

Conclusion: These procedural hurdles and substantive boundaries ensure constitutional amendments reflect deliberative consensus while preserving democracy’s foundational principles.